Broken discipline tracking systems let teachers flee troubled pasts

Feb 15, 2016 :: Georgia officials revoked a teacher’s license after finding he exchanged sexual texts and naked photos with a female student and was involved in physical altercations with two others.

A central Florida teacher’s credentials were suspended after she was charged with battery for allegedly shoving and yelling at a 6-year-old student.

In Texas, a middle school math teacher lost his job and teaching license after he was caught on camera allegedly trying to meet a teenage boy in a sting set up by NBC’s nationally aired TV program To Catch a Predator.

All three of those teachers found their way back to the front of public school classrooms, simply by crossing state lines. They’re far from alone.

An investigation by the USA TODAY NETWORK found fundamental defects in the teacher screening systems used to ensure the safety of children in the nation's more than 13,000 school districts.

The patchwork system of laws and regulations — combined with inconsistent execution and flawed information sharing between states and school districts — fails to keep teachers with histories of serious misconduct out of classrooms and away from schoolchildren. At least three states already have begun internal investigations and audits based on questions raised during the course of this investigation.

Over the course of a year, the USA TODAY NETWORK gathered the databases of certified teachers and disciplined teachers using the open records laws of each of the 50 states. Additionally, journalists used state open records laws to obtain a private nationwide discipline database that many states use to background teachers. The computerized analysis of the combined millions of records from all 50 states revealed:

- States fail to report the names of thousands of disciplined teachers to a privately run database that is the nation’s only centralized system for tracking teacher discipline, many of which were acknowledged by several states’ education officials and the database’s non-profit operator. Without entries in the database, troubled and dangerous teachers can move to new states — and get back in classrooms — undetected.

- The names of at least 9,000 educators disciplined by state officials are missing from a clearinghouse operated by the non-profit National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification. At least 1,400 of those teachers’ licenses had been permanently revoked, including at least 200 revocations prompted by allegations of sexual or physical abuse,

- State systems to check backgrounds of teachers are rife with inconsistencies, leading to dozens of cases in which state education officials found out about a person’s criminal conviction only after a teacher was hired by a district and already in the classroom. Eleven states don’t comprehensively check teachers' work and criminal backgrounds before issuing licenses, leaving that work to local districts — where critics say checks can be done poorly or skipped.

Problematic teachers amount to a minuscule proportion of the millions of educators nationwide. There are more than 3 million teachers nationwide, and less than 1% have ever faced a disciplinary action.

Despite years of efforts by child safety advocates and some U.S. lawmakers, the federal government does not play a role in mandating teacher background checks or making sure information about even severe abuse cases is shared between states. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, have a central government system to track disciplined teachers across jurisdictions.

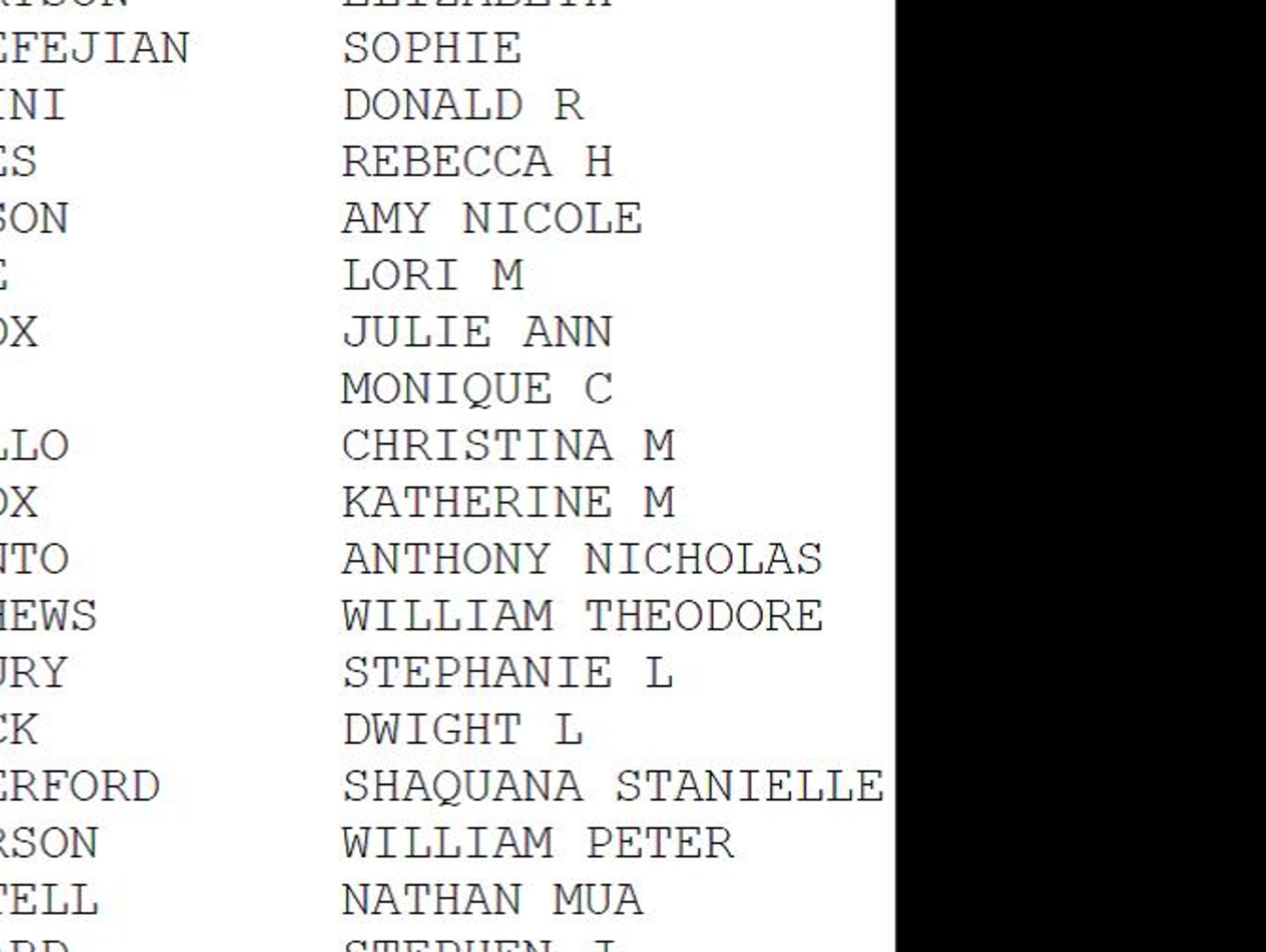

A USA TODAY NETWORK INVESTIGATION: The U.S. government does not

maintain a national database listing all teachers who permanently lost

their licenses.

Ramon Padilla and Berna Elibuyuk, USA TODAY.

“We dropped the ball by not doing so,” Ratcliffe said.

Officials in several more states also said they would fix some disciplinary actions that USA TODAY's analysis revealed were missing from the NASDTEC Clearinghouse. Georgia's teacher credentialing agency added new layer of oversight to its reporting process, and officials in Iowa also promised a complete audit of their system, as a result of discrepancies revealed by this analysis.

NASDTEC Executive Director Phillip S. Rogers said he believes the privately-run system works to prevent many troubled teachers every year from reaching classrooms, but he concedes the database is only as good as the data submitted by state agencies. The analysis found the national database is not only incomplete, but rife with misspellings and other inaccuracies that undermine its usefulness.

“It’s imperfect,” he said, “but it’s very close to being right most of the time.”

To others, an imperfect system is not good enough.

“When parents put their kids on the school bus in the morning, they have every right to expect that their kids are going to the safest possible environment,” said U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., who has pushed federal reforms. “And we’re not doing our job if we could make that environment safer."

Flaws in the nation’s fractured systems for checking teachers' backgrounds are apparent in the stories of educators like Alexander M. Stormer.

Stormer left a troubled past in Georgia to teach in Charlotte until last month, when North Carolina officials were contacted for this story.

In March 2015, Stormer resigned from Atlanta Public Schools after a string of misconduct allegations over a one-week span, according to separate accounts in state education department and police records. Stormer allegedly injured a student’s arm while dragging him from a desk into a hallway and pushed a girl in the chest into a wall. A surveillance camera captured the shoving incident.

The state education department and Atlanta police also reported that Stormer sent improper text messages, including naked photos, to another female student, according to records. In one text message exchange, the records say Stormer asked the student for sex.

Despite the problems in Georgia, Stormer applied for and got teaching licenses in South Carolina and North Carolina. South Carolina was later alerted to his discipline in Georgia by an update to the NASDTEC Clearinghouse, and the state revoked his South Carolina license.

In North Carolina, however, Stormer’s past went undetected. He taught at Phillip O. Berry Academy of Technology in Charlotte until last month, when he was suspended without pay after a reporter for the Asheville Citizen-Times (part of the USA TODAY NETWORK) began asking questions about why he had a North Carolina license and a teaching job after his license was revoked in two neighboring states.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district spokeswoman Renee McCoy said officials there would like a tool to more easily identify educators who have had problems elsewhere.

“It would be our hope that your story might inspire a national teacher license clearinghouse that would list license revocations from any and all states, so that districts would only need to enter a name and any revocation from any state would pop up,” she wrote in an email. Attempts to reach Stormer by phone, e-mail and at the home he owns were not successful.

There are plenty more examples across the country of teachers keeping damaged careers afloat by migrating to new states.

In April 2006, the Florida Department of Education notified Lainie Wolfe it sought to discipline her for a range of accusations including allegedly failing to follow school board policies after receiving a student’s suicide note; making false charges against her principal; and forging the signature of a parent on a student consent form. Florida later suspended Wolfe’s license for two years. Before the action was finalized, Wolfe applied for and was granted a teaching license in Colorado.

When Colorado officials found out years later about the Florida suspension, Wolfe signed a settlement deal in 2011 that is the equivalent to the permanent revocation of her Colorado license.

But Wolfe wasn’t finished teaching. She returned to Florida and was hired by Miami-Dade Public Schools. In 2012, according to Florida records, she “slapped (a) developmentally delayed 6-year-old student” in the face and was fired. Her license is now permanently revoked in Florida and Colorado.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Wolfe said she received glowing recommendations in both states for counseling and teaching, and she disputes many of the accusations against her. Though she denies slapping a student at the Miami school, Wolfe admitted she erred in failing to disclose the pending Florida disciplinary action when she applied for a Colorado license.

"I made a mistake," she said. "I should have disclosed."

Reva Diane Inabnett resigned from a Florida school district in 2012 after allegations that she shoved a 6-year-old led to a battery charge, which was dropped after she completed a deferred prosecution program. Inabnett’s license is suspended in Florida, state records show. She remained licensed in Louisiana and relocated there to teach at Webster Parish schools in 2013. She was teaching in Webster until Feb. 8, when she resigned after an inquiry to the district from USA TODAY.

"The district was aware of nothing that would have impaired her employment in the state of Louisiana, or obviously they would not have hired this lady or any other person," said Jon Guice, attorney for the Webster Parish School Board. "They take their obligations seriously."

In an email, Inabnett said she erred in judgment in Florida, and it was exaggerated. “I learned from my mistake. I did a great deal of soul-searching,” she wrote, adding that she taught successfully in Louisiana for three years. “I realized that we all make mistakes and that I needed to be more careful. I sought a second chance, and got it.”

Sometimes, troubled teachers who relocate find their pasts impossible to escape forever.

|

| Stanley A. Kendall worked as a teacher in Indiana after losing his teaching license in Texas. (Photo: Collin County Sheriff's Office) |

On camera, Kendall talks at length with the host, apologizing for chatting online about planned sex acts with someone he believed was a young boy and had arranged to come meet in person. "I am truly sorry," he says on the show, stressing he never hurt a student. Police arrested him, but prosecutors chose not to pursue criminal charges against Kendall or anyone else from that episode's sting. The Texas Education Agency permanently revoked Kendall's license the following year for "sexual misconduct," state records show.

However, the televised incident didn't stop him from teaching again. Kendall was hired as a substitute teacher by several Indiana school districts, where he worked unnoticed until someone saw a rerun of the TV show, recognized him and notified schools. A complaint was filed against his Indiana license and state officials investigated. In November 2014, Kendall and the state signed a voluntary license revocation, according to Indiana records.

“TEA pulled my license when they really didn't have grounds to, but they did, and I let it happen because I didn't have money to fight it,” Kendall said in an interview this week. “Teachers don't make a lot of money in Texas."

Rogers, of the clearinghouse operator NASDTEC, said no one attempted to quantify how many names are missing from the database. But, he said, there are countless incidents where the system has done its job.

“What we don’t know is how many people it has stopped. Because obviously it’s a significant number,” he said. “We don’t keep up with the number of people who have applied to a state and were denied a certificate because they were in NASDTEC.”

Background checks and the sharing of misconduct information are inconsistent state to state. In 11 states, background checks are primarily the responsibility of school districts or schools — not the state agency issuing teaching licenses. New Mexico, Nebraska and Indiana said their teacher-licensing agencies do not check all applicants against the NASDTEC Clearinghouse for past disciplinary action.

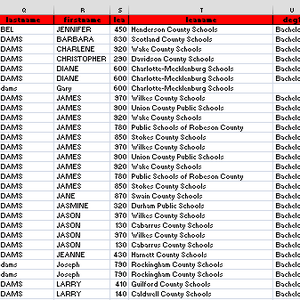

|

| A redacted version of the NASDTEC database obtained from Florida's education agency. (Photo: USA TODAY) |

In 2010, the Government Accountability Office, Congress’ watchdog agency, reviewed 15 cases in which a school hired an employee with a history of sexual misconduct. The GAO found at least six of those educators used a teaching position to target more children.

In a second report in 2014, the GAO found child abuse by school personnel is not systematically tracked by any federal agency, and the systems used to check backgrounds of educators “varied widely” between states.

In November 2015, an Arizona Department of Education report found about 22% of 704 educators disciplined by the state since 1996 were not in NASDTEC's Clearinghouse.

“The bottom line is the system that has been created is flawed,” Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Diane Douglas told the state's Board of Education in December. “And until we fix that root problem, we can never assure that we will be able to follow up on these things with 100% accuracy."

Over the past decade, there have been many federal government proposals to mandate background checks for teachers, require states and districts to share data about disciplined teachers and prohibit school districts from facilitating the transfer of a teacher accused of sexual misconduct to another jurisdiction. Among the proposals: requiring names of teachers disciplined for sexual misconduct be submitted to a national, government database.A bill introduced by then-Congressman Adam Putnam, R-Fla., would have required the U.S. Department of Education to develop a database of teachers found to have engaged in sexual misconduct and make it public. The measure would have put the USA closer in line with nations such as the United Kingdom, where the government maintains a national database of teachers barred from working with children.

“Our classrooms deserve much more than a piecemeal effort that leaves our nation’s schools exposed to predators moving from state to state,” Putnam said in a speech in Congress in 2009. The bill never got a hearing. Nevertheless, advocacy and education policy groups continued to push for a more reliable way to share teacher misconduct information between states.

“It’s really about protecting kids,” said Sandi Jacobs, senior vice president for state and district policy for the National Council on Teacher Quality. “It seems we could come up with a clear, consistent set of terms and rules so that information is easily shared across states.”

Contributing: Tonya Maxwell of the Asheville Citizen-Times, Chelsea Schneider of The Indianapolis Star, Jason Clayworth of The Des Moines Register, John Kelly and Nick Penzenstadler of the USA TODAY NETWORK, Michelle Boudin of WCNC in Charlotte, Dillon Collier of KENS in San Antonio, Jeremy Jojola of KUSA in Denver, Rebecca Lindstrom of WXIA in Atlanta, Lechelle Yates of WFMY in Greensboro, N.C., Russ Walker and Linda Byron of KING in Seattle and Anne Schindler of First Coast News in Jacksonville.

No comments:

Post a Comment