Sarah Carr The Atlantic | http://theatln.tc/11paE7T

All photos by William Widmer

Nov 17 2014, 9:36 AM ET :: From the moment Summer Duskin arrived at Carver Collegiate Academy in New Orleans last fall, she struggled to keep track of all the rules. There were rules governing how she talked. She had to say thank you constantly, including when she was given the “opportunity”—as the school handbook put it—to answer questions in class. And she had to communicate using “scholar talk,” which the school defined as complete, grammatical sentences with conventional vocabulary. When students lapsed, they were corrected by a teacher and asked to repeat the amended statement.

There were rules governing how Summer moved. Teachers issued demerits when students leaned against a wall, or placed their heads on their desks. (The penalty for falling asleep was 10 demerits, which triggered a detention; skipping detention could warrant a suspension.) Teachers praised students for shaking hands firmly, sitting up straight, and “tracking” the designated speaker with their eyes. The 51-page handbook encouraged students to twist in their chairs or whip their necks around to follow whichever classmate or teacher held the floor. Closed eyes carried a penalty of two demerits. The rules did not ease up between classes: students had to walk single file between the wall and a line marked with orange tape.

And there were, predictably, rules governing how Summer dressed. Carver Collegiate’s coed code called for khaki pants pulled up to the hip; a black or brown leather (or imitation-leather) belt; a school-issued polo shirt with the collar turned down; a white or black undershirt; and no hats, sunglasses, sparkles, flash, or bling of any kind. Students could be barred from class for wearing the wrong kind of shoe, such as the popular Air Jordans; the code mandated specific colors, styles, and brands, Adidas and Chuck Taylor among them.

Summer was a high-school freshman, 14 years old. “It felt like I was in elementary school,” she said, where in fact she had had it easy by New Orleans standards: she’d been spared the silent lunches and embarrassing punishments her peers at some other schools had endured. At Carver, Summer quietly rejoiced whenever she discovered a way to assert her individuality without breaking code, like wearing purple lipstick.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of elementary and middle schools across the country have embraced an uncompromisingly stern approach to educating low-income students of color. But only more recently have some of the charter networks that helped popularize strictness, including the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP), opened high schools—an expansion that has tested the model in new, and divisive, ways. There’s no official name for this type of school, and not all of the informal terms please the educators in charge: the ethos is often described as “no excuses,” “paternalistic,” or devoted to “sweating the small stuff.” The schools, most of them urban charters, share an aversion to even minor signs of disorder and a pressing need to meet the test-based achievement standards of the No Child Left Behind era or else find themselves shuttered. Front and center in their defense of intensive regimentation for their predominantly minority students is a stirring goal beyond that bottom line: to send all their graduates, many of them first-generation college aspirants, on to higher education.

“You have to be hard and strict,” a parent urged the principal. “You can’t be soft, because you know how these kids are.”

Yet a growing array of critics is concerned that the no-excuses approach more effectively contributes to very different results: a flagrant form of two-tiered education and a rise in racially skewed suspension and expulsion rates for low-level misbehavior—a trend that Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has railed against repeatedly over the past year. Some go further, arguing that those taped lines point the way to prison rather than to college—that the harsh discipline is a civil-rights abomination, destined to push too many kids out of school and into trouble with the law. For the families involved, particularly the students, the story is more complicated. Many of them come to appreciate the intense structure, but only if they also come to trust the mostly young educators who enforce it. As school leaders in New Orleans are discovering, forging that trust is far harder than teaching someone to say thank you and toe an orange line.

Ben Kleban, the founder and CEO of New Orleans College Prep, grew concerned about a suspension rate that exceeded 50 percent, and began rethinking disciplinary policies.

New Orleans schools, which have taken the experiment with paternalistic public education to a new extreme, have been at the forefront of extending regimented discipline to the high-school level. After Hurricane Katrina devastated the region in 2005, the city became a proving ground for the most popular and contentious reforms. The charter-school movement grew, spreading a heavy reliance on alternative teacher-recruiting programs like Teach for America—and, not least, a commitment to comprehensive, punitive discipline policies very different from the pedagogical flexibility and emphasis on individual expression favored by many traditional education schools.

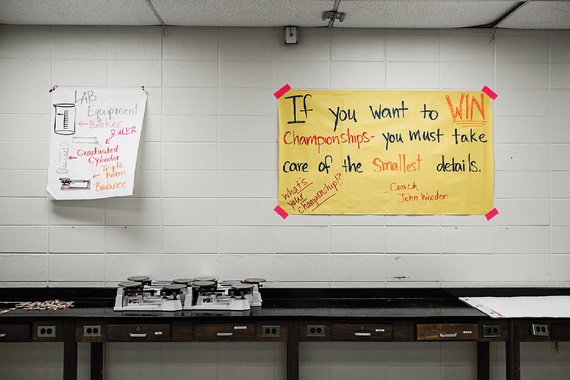

In step with an energetic breed of charter advocates nationally, the reformers who descended on New Orleans were convinced that progressive pedagogy and discipline had an especially sorry record in low-income districts, where many children faced more than their share of disorder and violence. Chaotic classrooms, the newcomers argued, were a major reason schools floundered and failed. The controversial broken-windows theory—which holds that a firm response to minor signs of disarray, like broken windows, is essential to inhibiting more-serious criminal activity—was the reigning analogy, invoked by top administrators on down. No infraction was too small to address. A uniform violation, I heard one high-school teacher remark, “means a broken window, which means a broken path to college.”

There was no better place to apply this theory than New Orleans, where, the year before Katrina, about two-thirds of schools failed to meet Louisiana’s standards for acceptable performance, defined largely by test scores. By one estimate, based on a combination of local, state, and federal data, 5 percent of the city’s black public-school students went on to graduate from college. Former students and teachers told too many stories of decrepit buildings where hallways reeked of marijuana, burned-out teachers slept through class, frightened students carried weapons for self-protection, and few people talked about college.

Almost a decade has passed since reformers began overhauling the school system, and academic performance has improved citywide: nearly two-thirds of students in grades three through eight currently meet state proficiency standards. Graduation-rate data, several researchers agree, still aren’t solid enough to cite. Yet along with the growth in achievement has come plenty of debate about what is driving it. As New Orleans students who entered kindergarten after Katrina make their way into the city’s new high schools, Summer Duskin isn’t the only one questioning the doctrinaire approach to discipline. Some educators themselves are wondering whether it has become an obstacle to progress.

Erin Lockley at first bridled at her school’s stern tactics, but now, in her senior year at Cohen College Prep, she feels the approach can work if students are given more of a voice as they get older.

Idealistic and ambitious young charter-school leaders like Ben Kleban and Ben Marcovitz arrived in New Orleans as fervent believers in an unwaveringly firm approach. “In 2007–8, if a student had a stripe on their sock or a mark on a shoe, there was a consequence,” says Kleban, who was 27 when he founded New Orleans College Prep seven years ago, admitting sixth-graders who this year became the first batch of 12th-grade graduates at Kleban’s high school, Cohen College Prep. As a student named Erin Lockley quickly discovered upon her entry into New Orleans College Prep in 2008, her teachers meant business. After hastily pulling on a green undershirt on the first day, rather than the requisite black or white one, she was barred from class until she changed it—and she had to write out her multiplication tables (from one to 14) 10 times that night as punishment.

Ben Marcovitz—now 35 and the CEO of Collegiate Academies, which runs three charter high schools, among them Carver Collegiate, Summer’s school—embraced stringent discipline and character education, too, when he launched the first of his trio, Sci Academy, in 2008. And in 2010, KIPP opened a high school in New Orleans, among the first for the charter network, which initially focused just on the middle grades and now encompasses more than 160 schools nationally. As part of its college push—KIPP’s current, ambitious target is bachelor’s degrees for three-quarters of its graduates—the network decided to extend its hyper-structured approach straight up to the college door.

At the inaugural parents’ meeting, in late August of 2010, the administrators of the new KIPP high school, called Renaissance, didn’t have a hard sell. Dozens of eager mothers, plus a few fathers, had climbed two flights of stairs on that sweltering evening to listen to the school’s 31-year-old principal, Brian Dassler, describe his vision for the school. Several parents fanned themselves with copies of the school’s so-called discipline matrix, and the audience cheered him on as he outlined the school’s “no idling” policy. After Dassler noted that the Renaissance staff hadn’t been vigilant enough about preventing the students from rolling up the sleeves of their uniforms, a mother shouted, “Get even stricter, Mr. Dassler! Do it!” Another chimed in, “You have to be hard and strict. You can’t be soft, because you know how these kids are.”

For the many parents who shared the charter founders’ big dreams of college, those hopes went along with a more immediate concern: keeping their children safe. As the sociologist Annette Lareau documents in Unequal Childhoods (2003), low-income parents as a group tend toward a firmly directive approach with their children, whereas middle-class parents typically favor a more solicitous tack, encouraging their kids to question adult authority. Lareau takes note of the different effects on behavior: dutiful respect versus a sense of entitlement.

As adolescence arrives, strict enforcement gets harder, but no less urgent in the eyes of many families in urban settings like New Orleans—and for good reason. Children growing up poor and black in the city are more likely to witness gun violence and street drug sales than their middle-class peers are. Once teens, they are more likely to attract the suspicion of the police, to be arrested if they break the law, to spend their lives behind bars, and to die young. If they make a mistake—fall in with the wrong crowd, antagonize the wrong adults, drop out of school—they are less likely to get a second chance. One study found, for instance, that marijuana use among whites is slightly higher than among blacks, yet blacks are arrested for it nearly four times as often. “The margin for error is much smaller in black communities, especially for black boys,” Troy Henry, a New Orleans parent, told me, defending an even tougher approach to keeping kids on the straight and narrow at the mostly black Catholic school where he served as a board member until this summer: corporal punishment.

Worries about jobs play a role, too. For generations, the New Orleans public schools have graduated countless students straight into low-paying work in the tourism business. With only a few exceptions, the industry’s dishwashing, housekeeping, and other positions are nonunionized and come with little job security. Employees who make even a small misstep can be speedily replaced with new hires who don’t show up late, forget their uniform, or talk back to customers—as anxious parents are well aware. “If you mess up once at Harrah’s [a New Orleans casino], you are going to be fired!” a parent called out during the KIPP Renaissance meeting. A sense of entitlement, she knew, wouldn’t take these workers far; a willingness to learn and follow the rules was essential.

Students at KIPP Renaissance liked to joke that the charter’s acronym stood for the Kids in Prison Program. But a slim 15-year-old I met in 2010 shared some of the same hopes nursed by resolute reformers: that the no-excuses ethos could be the key to rescuing, rather than winnowing out, the toughest cases. Brice, whose last name I agreed not to publish, signed himself up for KIPP Renaissance because of—not in spite of—the rules. He’d already been expelled from one school and could feel himself getting pulled into the drug scene in Hollygrove, the working-class New Orleans neighborhood where he lived with his mother. He was desperate for structure that would keep him from getting into more trouble, and keep other troublemakers away from him. Brice told me, “You got to be really big and really on top of your game to make me do what you want.”

Yet a rigid focus on rules also turns out to put students at risk in ways that they and their parents, and educators as well, don’t always anticipate. The use of out-of-school suspensions has soared at schools of all types since the 1980s, when a “zero tolerance” policy similar to the no-excuses approach became popular in noncharter schools. Drawing on suspension and test-score data in North Carolina, one economist recently concluded that the approach can help principals “maximize achievement,” because students profit when disruptive classmates are removed. But an American Psychological Association report in 2008 offered a different view. The authors found no evidence that high rates of suspension or expulsion improve either student behavior or school safety, much less the educational climate: even controlling for a variety of demographic factors, the research they cited showed declines in academic achievement.

And the zealous disciplinary tactics at the paternalistic charters that are overrepresented in poor urban districts contribute to persistent racial gaps in students’ experience. Starting in preschool, black children are suspended and expelled at far higher rates than white students are, despite little objective evidence that they behave any worse. The discrepancy persists as children get older and the number of overall suspensions rises. In high school, black students are more than three times as likely as white students to get suspended at least once. Untangling causation and correlation is obviously no easy matter, but one statewide study in Texas reported that students suspended or expelled for a “discretionary violation”—having a bad attitude, for example—were nearly three times as likely to come into contact with the juvenile-justice system the following year. Ramifications like these have spurred several large urban districts (Baltimore, Los Angeles, Chicago) to take aggressive measures over the past couple of years to curb discretionary discipline tactics. Schools have begun banning suspensions, for instance, for vaguely defined offenses like “willful defiance,” which can contribute to the troubling racial disparities, several experts have concluded.

In New Orleans, too, alarming numbers have begun to prompt challenges to and reassessments of charters’ no-excuses regimens. In 2012–13, their first academic year, Carver Collegiate and its sister school in Ben Marcovitz’s trio, Carver Prep, led local high schools in suspension rates—this in a city where suspending more than a fifth of a school’s students each year is not uncommon. At Carver Collegiate the figure was 69 percent, and at Carver Prep it was 61 percent; the national average for high schools was 11 percent. School officials said 80 percent of suspensions lasted for just a single day. Yet several students complained that they were sometimes sent home “off the books,” with nobody documenting the dismissal and minimal or no inquiry into the circumstances that led to the misbehavior. Disputing their accounts, Marcovitz emphasizes that Collegiate Academies strives to be as accurate as possible with its data. At KIPP Renaissance, the discipline so eagerly welcomed soon proved ineffectual, and many parents’ support eroded. Several years after he founded New Orleans College Prep, Ben Kleban became disturbed by a suspension rate that exceeded 50 percent as his first students made their way into Cohen College Prep High School.

A report found no evidence that high rates of suspension or expulsion improve student behavior or school safety.

Some have called the problem “the progress trap”: when systems designed to help students catch up start holding them back instead. As Elizabeth Green recounts in her new book, Building a Better Teacher, educators in some charter schools around the country quietly began questioning the rigidly rule-based mentality—in themselves and in their students—around the time reform in New Orleans was getting under way. If mutely regimented middle-school students turned into rowdy bus riders a couple of years later, what did that say about the no-excuses theory in practice? The students were testing boundaries, as of course older kids do, yet the no-excuses culture was intended to be cumulative. The overarching goal was not to exact obedience for obedience’s sake, or merely to chalk up short-term gains in test scores, and it certainly was not to encourage teachers to be tyrants. The point was to develop increasing self-control in students en route to graduation. In college, after all, the ability to think critically and navigate coursework independently counts for much more than reflexive compliance.

Kleban, who faced a 62 percent suspension rate at Cohen College Prep in 2011–12, found himself reexamining the behavior policies at his charter chain with such concerns in mind: he wanted to prepare his oldest students for autonomy—without scaling back too much on structure. Besides, suspensions weren’t working for many students. Fourteen percent of students were barred from campus just once, a single suspension was all it took to jolt them into improved behavior; another 13 percent were suspended twice. But 35 percent of students were sent home three times or more; they clearly weren’t getting the message.

“There’s a value in being consistent,” Kleban says, and the no-excuses and zero-tolerance approaches have the benefit of clear-cut implementation—a tidy matrix or rule book. “But the reality is, kids are different,” and problems arise “when students feel like something is being done to them and they don’t understand why.” At Cohen, the principal and other administrators held town-hall meetings where they solicited students’ views on school rules, and then hammered out compromises. The student government drafted a new outerwear policy (more sweatshirt options) and spelled out the penalties for breaking the revised rules. Behind the scenes, the principal has gotten to know the students well enough to customize discipline when appropriate—overlook a uniform violation, for example, and help a student get an item of clothing when a family is going through a rough patch financially. School officials also inaugurated extracurricular activities students said they wanted, along with more pep rallies and other celebratory events.

Erin Lockley, who had bridled at the punishment for wearing the wrong undershirt as a sixth-grader, is now a senior who credits the no-nonsense ethos with teaching her self-discipline. She feels the approach can work if students are given a voice, particularly as they get older. Teachers—“most of the time … coming from New York or further out,” she says—understand that “they have to meet us halfway.” Sometimes that’s as simple as talking less and listening more. Kleban and his staff still wrestle with the appropriate balance of structure and flexibility. But he says he hears fewer complaints about the charter network’s disciplinary practices. And by 2013–14, the suspension rate at Cohen had fallen to 37 percent, with the proportion of repeat offenders plummeting.

A rocky first year at KIPP Renaissance exposed the discipline matrix as no guarantee of the orderly school parents had been hoping for. Brice was an extreme: a repeat offender who eventually goaded a frustrated young principal to enforce a 45‑day suspension, a rare move at even the strictest schools—and a patently risky one. As Brice himself could have predicted, a month and a half at loose ends all but ensured that he would fall deeper into a dangerous scene in his neighborhood, which he did. He returned to school, but soon ended up in jail, and has been in and out of prison ever since. KIPP, meanwhile, has struggled with staff turnover—five principals (among them, one interim and two who shared the role)—further eroding something no less important than disciplinary consistency: a sense of a school community. A spokesperson for KIPP New Orleans says the school has made significant progress in staff retention over the past year, and adds that the school has modified its disciplinary practices, learning from past mistakes. With the goal of suspending students “only as a last resort,” a team of administrators now decides whether the move is warranted. The suspension rate has fallen dramatically, and Renaissance, he says, is in a “very different place than it was in 2010.”

At Collegiate Academies, where Summer Duskin had balked at strictures she felt she’d outgrown, Ben Marcovitz has been struggling too. On the positive side, he points to Sci Academy, the first high school in his network, as proof of success: though attrition has been high (its initial class shrank 37 percent over the school’s first two years), some of the students who make it through end up accepting—even appreciating—the strictness, and more than 90 percent go on to graduate and enroll in college. Yet last winter, Marcovitz and his staff faced a series of student protests at Carver Prep and Carver Collegiate. At the same time, a civil-rights complaint filed by students and parents asked state, federal, and local authorities to investigate the schools’ disciplinary policies, alleging abuse of students with special needs and overuse of suspensions for trivial matters. Marcovitz says the allegations “were shocking to me and completely uncharacteristic of our entire philosophy and approach.”

Summer—who had received countless demerits and three out-of-school suspensions in her first semester as a freshman—was among the roughly 60 students who walked over to a nearby park wearing orange wristbands that read Let me explain. In a letter of demands she helped write, the teenagers lamented, “We get disciplined for anything and everything.” High on their list of complaints were the stiff penalties for failing to follow the taped lines in the hallways, for slouching, for not raising their hands with ramrod-straight elbows. “The teachers and administrators tell us this is because they are preparing us for college,” the students wrote. “If college is going to be like Carver, we don’t want to go to college.”

Marcovitz believes some of the students’ claims were exaggerated, and he makes a point of noting the praise that counters the stern rebukes, the warmth that accompanies the structure. But by the summer, he was ready to tackle what he casts as the next challenge in the reform project: if Sci Academy was evidence of what stringent discipline could help achieve, now his high schools would pursue the same results through gentler means. “While it was extremely tough to hear so much concern about our program, we took it as a mandate from the community,” he says, and maintains that high suspension rates already had his attention. He committed the Collegiate Academies leaders to zero out-of-school suspensions in the 2014–15 school year. “We don’t know how to do this yet,” Marcovitz admitted before classes began. There will inevitably be stumbles, he acknowledged, as they explore an array of alternatives, from partnerships with juvenile-justice groups in the city to “restorative justice” strategies that get students talking through problems rather than simply paying penalties. The new ethos will require “relationships being very clearly built” and “love being very clearly expressed.” But apart from that, he and his staff are forging ahead largely without a rule book, and so far they report having issued a handful of suspensions.

The change came too late for Summer, who had already transferred to McDonogh 35, which opened nearly a century ago as the city’s first public high school for black students. Many of the city’s young school reformers dismiss the contemporary McDonogh 35 as chaotic and poorly run, and its academic reputation has slipped in recent years. But its legendary history—Ernest Nathan Morial, the city’s first black mayor, was one of many local African American leaders nurtured within its walls—undergirds an ethos of pride and engaged purpose that Summer and her family had lost sight of at Carver Collegiate. The strictness wasn’t the main issue, at least not for Summer’s father—he attended an all-boys Catholic high school in New Orleans that was, if anything, stricter. The problem, as he puts it, is that “I can’t get my mind around these folks to see what’s the point.” School disciplinarians had failed to cultivate a shared sense of direction and the trust that goes with it. When that happens, he agrees with his daughter, even the most well-intentioned system can end up feeling like “a blind application of rules.”

No comments:

Post a Comment