Background:From Maddy Daily

Major issues remain as California budget deadline nears -- Gov. Jerry Brown and his fellow Democrats in the Legislature continue to negotiate on several items in the California state budget for the fiscal year beginning July 1. Any plan has to be approved by Monday, the constitutional deadline for the Legislature to act. A joint legislative budget-writing committee worked into the evening Tuesday. Sacramento Bee article; Capital Public Radio report; LA Times article

New school funding formula to get huge increase

Jun 9, 2015 | By John Fensterwald | EdSource |

California Department of Finance

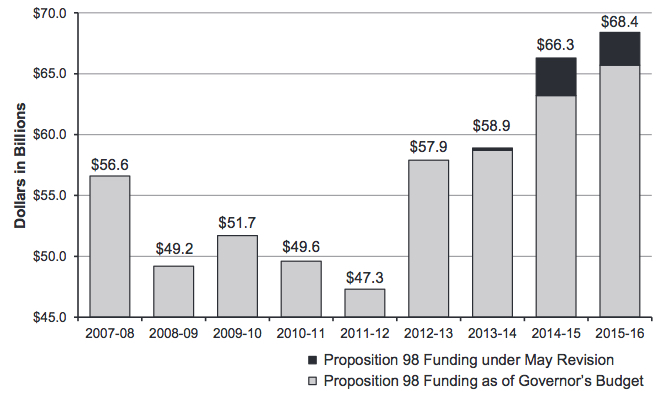

Proposition

98 funding for K-12 schools and community colleges has recovered

dramatically since the low of $47 billion in 2011-12 to what would be a

high of $68.4 billion next year. The black bar represents revised

estimates of Prop. 98 revenue for three years in Gov. Brown’s May budget

proposal.For the budget year starting July 1, Gov. Jerry Brown is proposing an additional $6.1 billion for the Local Control Funding Formula, the funding system that shifts more authority over operating budgets to local school boards. It also steers more dollars to “high-needs” students – English learners, low-income children and foster youth. The new dollars will take districts much closer, after only three years, to what the Legislature set as full funding when it passed the funding law in 2013.

The Legislature defined full funding as the end of a transition period from the old revenue distribution system, where districts were funded unequally, based often on outdated formulas and a grab bag of earmarked funds, called categoricals, to one where, with few exceptions, funding would be uniform. All districts would receive the same base funding per student, with supplemental dollars flowing to districts according to the proportion of their high-needs students.

Brown’s proposed increase will bring the total for the Local Control Funding Formula to $53.1 billion. That’s about $6 billion ahead of schedule, according to the state Department of Finance. By one measure, that equals 90 percent of full funding, currently estimated to be $60 billion. By another measure, it’s 70 percent of the way there (see graphic below for an explanation of the difference).

Of K-12 funding from Proposition 98, the main source of revenue for K-12 schools and community colleges, 79 percent will be distributed to districts through the funding formula next year, with the rest allocated for community colleges, special education, child nutrition and a few other state programs.

Some longtime education observers are cautioning districts not to waste an unprecedented spending opportunity that is not likely to come again anytime soon.

“This is the moment when districts should be placing bets on where they want to be in 2020 to do the most good for their students,” said David Plank, executive director of Policy Analysis for California Education, or PACE, a research center based at Stanford University.

The vehicle for setting priorities is the Local Control and Accountability Plan, a document that districts are required to update annually after soliciting the views of parents and the community. In an LCAP, districts list performance goals, metrics to gauge progress and how much they will spend to achieve the goals. Each district’s LCAP must be submitted to the county office of education by the start of the new fiscal year on July 1.

Arun Ramanathan, CEO of Pivot Learning Partners, a nonprofit education consulting firm based in San Francisco, said that districts would be wise to invest in a few strategies that could be sustained for the next several years, such as increasing learning time by extending the school year to reduce summer learning loss, adopting early reading strategies with professional development for teachers and choosing research-based approaches to student discipline. He is worried that districts won’t do that, in part because the LCAP requires districts to respond to eight priorities, including school climate, parent involvement, academic achievement and student engagement.

A lack of clear priorities, he said, could lead “to marginal investment in many areas, with few districts making deep investments.” Scattershot choices might not survive an economic recession or the end of temporary taxes under Proposition 30, which has produced as much as $8 billion in revenue per year. The Legislative Analyst’s Office, in its analysis of the first-year LCAPs, expressed the same concern.

Michael Hanson, superintendent of Fresno Unified, the state’s fourth-largest district with 73,000 students, said that it would be a mistake for districts to automatically fund every pre-recession position and program it cut without seizing the opportunity for new priorities. Having made big budget cuts during the recession, Fresno Unified decision-makers “were clear-eyed and sober” in thinking about how to spend money when it returned, he said.

At its June 2 meeting, the Fresno Unified board passed a budget with $35 million in new money under the Local Control Funding Formula and an additional $28 million in one-time funding. That money, a 12 percent increase, will continue new school strategies that will affect every grade, Hanson said. Changes will include extending preschool to 80 percent of low-income children in the district and extending the instructional day by a half hour – 18 days over the course of the year – in two-thirds of elementary schools with high proportions of low-income students and English learners. Middle schools will offer more courses required for college admission, and the week will be restructured to allow more time for teachers to work together. The focus in high school will be significantly expanding career technical programs and career pathways, including starting a new school for 10th- to 12th-graders focusing on entrepreneurship.

Smaller classes

An acceleration in funding will also affect how soon districts need to reduce class sizes in kindergarten through 3rd grade. The big increase that Brown proposed in the revised May budget – $2.1 billion more than in his original budget in January – caught districts by surprise, said Ron Bennett, School Services’ CEO.The law creating the new funding formula requires districts to have no more than 24 students per teacher in K-3 grades by full funding. Class sizes would still be higher than the 20-to-1 ratio that the state had in place for the decade before the recession. But districts that have allowed elementary school classes to balloon to 30 kids or more per teacher following state funding cuts would have to hire many new elementary teachers.

The law requires districts to lower class sizes in proportion to increases in funding under the formula. Brown’s proposed $53.1 billion for the formula would mean that districts should be about 70 percent of the way to reducing to 24-to-1 next year – from whatever class sizes they had in place in 2012-13. Districts that fail to reduce their class sizes proportionally in every K-3 school risk losing 10.4 percent of their funding for being out of compliance: $737 per student.

Many districts that had already begun planning for K-3 classes for next year based on the smaller January budget will struggle to meet the new class size ratios on such short notice, Bennett said. They may not have space for more classrooms, and they will have to reassign or hire more staff, then train them for the opening of school. “Some districts are panicked,” he said.

However, the law does permit an exemption: Teachers in a district can vote to waive the smaller classes each year. That’s what teachers in Stockton Unified did with the contract they ratified in April. In receiving a 12.5 percent raise effective July 1, some of it retroactive to 2013, they set class sizes next year at 31-to-1 for 1st through 3rd grades and 24-to-1 for kindergarten. That’s only one student less per class than in 2013-14. Class sizes will drop to 29-to-1 in 2016-17 under the agreement.

Some districts, such as Fresno, are already at 24-to-1 for K-3.

At full funding, the California Department of Finance says, 90 percent of school districts will receive no less than they got before the recession in 2008, adjusted for inflation. Many districts like Fresno, with large numbers of English learners and low-income students for which they receive extra funding, will be at or above that level next year.

Brown and lawmakers assumed that, with gradually increasing revenues and cost-of-living adjustments, it would take eight years, until 2020-21, to fully fund the formula. The Department of Finance is sticking with that projection, even though districts are well ahead of schedule at this point, said Thomas Todd, assistant program budget manager of the Department of Finance. In 2018-19, when temporary taxes from Proposition 30 are set to expire, the department is predicting only a 1 percent growth in revenue in the state’s three main sources of revenue – probably not enough to cover a cost-of-living increase. Revenues going to education could also take a hit in the event of an economic recession, Todd said.

Groups in the Education Coalition, including the California Teachers Association and the California School Boards Association, will push for either an extension of Prop. 30 taxing the wealthiest 1 percent of wage earners, or another tax to take its place. Brown, however, has repeatedly said he sold Prop. 30 to voters as a temporary tax and is committed to letting it expire.

Central Valley school districts differ on how to use money earmarked for disadvantaged kids -- School

districts across the valley are trying to figure out what to do with

new money intended to help their most vulnerable students. But a letter

from the State Department of Education raises questions about whether

some of their spending on things like teacher raises is allowed. The

interpretations of the new funding formula vary, based on who you ask. KVPR report

No comments:

Post a Comment