-

90% of persons who are unvaccinated or not immune from previously having measles will get sick if exposed to the virus – which is airborne.

-

If a school has a student with a confirmed case of measles, districts should send all unvaccinated students home.

By Jane Meredith Adams | EdSource | http://bit.ly/1zUyB6L

January 26, 2015 |The largest outbreak of measles in California in years is prompting school officials to redouble their efforts to convince parents to vaccinate their children.

Sheri Coburn, the president-elect of the California School Nurses Organization, said the push for immunization is “one positive thing” to come from the rash of cases – now at 73 statewide – of the highly contagious and sometimes serious illness. The majority of cases are linked to exposure to the measles virus at two Disney theme parks.

“We continue to advocate for people to be vaccinated,” Coburn said, noting that three-quarters of those who contracted measles were “not vaccinated at all,” referring to the Disney outbreak.

The push for immunization is ‘one positive thing’ to come from the measles outbreak, said Sheri Coburn, president-elect of the California School Nurses Organization.

State law requires children to be vaccinated for a variety of illnesses by the time they enter kindergarten. But parents may obtain “personal belief exemptions” from the required vaccinations, making their children more vulnerable to contracting potentially fatal illnesses and transmitting the viruses to others.

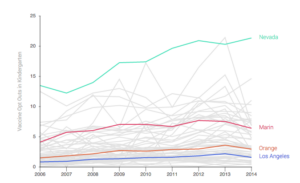

The proportion of parents seeking those exemptions varies greatly from district to district, and even from school to school, as noted in an earlier EdSource report.

The number of school-age children with confirmed cases of measles in California reached 13 on Monday. The outbreak has prompted many school districts to take action, including emailing measles alerts to parents, urging them to vaccinate their children if they haven’t already, and referring families to free immunization clinics.

In San Bernardino County, for example, public health and school officials collaborated on a letter that districts can send to parents or post on their websites. The letter recommends that children who have not had a measles vaccination “have that done,” said Dan Evans, spokesperson for the San Bernardino County Superintendent of Schools.

In the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District, where a freshman baseball coach contracted measles, school nurses and public health investigators last week quickly scrutinized the immunization records of baseball team members and found that all were up to date. Following advice from the Los Angeles County Public Health Department, the district did not exclude any students from school, regardless of their vaccination status, because exposure appeared to be limited.

However, parents have received letters from school nurses and the district superintendent, and in the case of Santa Monica High, a letter from principal Eva Mayoral urging that “all students be up to date with all immunizations.”

Los Angeles Unified’s District Nursing Communicable Disease Control Team has mobilized, with school nurses teaming up with county public health investigators to track suspected cases of measles; five cases have been investigated, but none of them has proved to be measles.

Nurses in the Laguna Beach Unified School District have sent letters to parents of unvaccinated students urging them to have their children immunized. And Oceanside Unified posted on its website a letter from the San Diego public health department encouraging vaccinations and thanking parents for taking steps to protect their families and the community from measles.

Even in Santa Clara Unified, far from Disneyland, the school district last week posted a message from the county’s public health department on its website that was both a call for calm and a call to action. Two cases of measles have been reported in Santa Clara County, both of them in adults.

“We want to reassure parents that there is no need to be alarmed,” the message on the website stated. “If your children have been vaccinated, they are protected from catching measles. However, a measles outbreak serves as an important reminder that everyone does need to make sure that they are either immune or have been vaccinated against measles.”

Dr. Gilberto F. Chávez, deputy director of the Center for Infectious Diseases at the California Department of Public Health, has made it clear that if a school has a student with a confirmed case of measles, districts should send unvaccinated students home.

“That is standard practice in this state,” Chávez said in a telephone press briefing. “If there is a child with measles in a school setting, the expectation is that the rest of the children who are not immunized need to be excluded from that school.”

So far, Huntington Beach High, with an enrollment of about 3,000 students, is the only known school where students have been sent home as a result of the disease.

A case of measles at the school came to light when a parent, whose unvaccinated daughter was sent home, appeared on a television news show to explain her child’s medical exemption to the measles vaccine.

Officials at the school initially notified 24 students that they would have to stay home because they were not vaccinated, but four of those students provided evidence of vaccination, said Pamela Kuhn, a certified school nurse and coordinator of health and wellness for the Orange County Department of Education.

News that the unvaccinated students were being kept at home has generated calls and emails overwhelmingly in favor of the decision to exclude unvaccinated children from attending classes, she said. “I’m getting more calls supporting our decision to exclude,” Kahn said.

The students will be out of school for 21 days, which is the length of time it takes before the measles could appear. They are scheduled to return to school on Friday.

Measles has been confirmed in patients from seven months to 70 years old by 11 county or local public health agencies: Alameda, Long Beach City, Los Angeles, Orange, Pasadena City, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Mateo, Santa Clara and Ventura, according to the California Department of Public Health. Earlier last week, before the numbers increased, the department said that 25 percent of the cases required hospitalization.

The “great majority” of the cases involve unvaccinated people, Chávez said.

The highly contagious virus was declared eradicated in the U.S. in 2ooo, but an increase in the number of parents choosing not to vaccinate their children has led to outbreaks, Chávez said. Parents who say it is safer not to vaccinate their children are basing their decision on “pure misinformation,” he said.

Going Deeper

- Under new state law, school nurses aim to stop rise in vaccination opt-outs, EdSource Today, April 6, 2014

- How vaccinated are California kindergarteners? EdSource Today vaccination app, 2013-14

- Measles, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Jane Meredith Adams covers student health and well-being. Email her or Follow her on Twitter. Sign up here for a no-cost online subscription to EdSource Today for reports from the largest education reporting team in California

_________________________________________

Once easily recognized, signs of measles now elude young doctors

By Eryn Brown , Rong-Gong Lin II and Rosanna Xia | LA Times | http://lat.ms/18q7FAj

A decades-long effort to immunize American children managed to wipe out the last homegrown measles cases in 2000. (Justin Sullivan, Getty Images)

27 January 2015 :: Some medical experts worry that the battle against measles has become a victim of its own success

It was spring of 2014. Dr. Julia Shaklee Sammons looked around and saw trouble.

An infectious disease specialist at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, she had read the headlines about new measles cases — including outbreaks in California and Ohio — and decided it was time to speak out.

Writing in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, Sammons implored doctors to get more familiar with the disease. In two tightly packed pages, she described measles' potentially deadly effects and outlined how to diagnose it. She included archival photos to drive her point home: A tow-headed boy covered in an angry rash in 1963. A child's upper lip pulled back to display tiny white spots, an early sign of measles that sometimes can lurk unnoticed.

She knew how badly coaching was needed.

Like many younger physicians, Sammons, who graduated from medical school in 2006, trained when the disease was no longer an issue in the United States. "I have not cared for a patient with measles," she said. "I hope I never have to."

A decades-long effort to immunize American children managed to wipe out the last homegrown cases in 2000. But the virus still can arrive here from other countries and spread.

Today — as California faces its largest outbreak since the disease was declared eliminated — some worry that the battle against measles has become a victim of its own success.

The virus is now so rare that medical schools don't dwell on it at length. Lack of familiarity can make medical providers, the vast majority of whom have never seen a sickened patient, slow to recognize the potentially deadly, and highly contagious, disease.

"Doctors aren't thinking about measles because they haven't seen it before," said Dr. Mark Sawyer, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist at UC San Diego and Rady Children's Hospital. "Diagnosis is delayed, the patient isn't isolated, and they end up managing to expose other people until somebody goes: 'Wait a minute — this is measles!'"

It's usually a senior doctor who sees it, Sawyer said.

The current outbreak began a week before Christmas and thus far has sickened at least 87 people in seven states and Mexico. About one in four of the 73 patients from California, who range in age from 7 months to 70 years, has required hospitalization. Most had visited Disneyland. Many were not immunized. A number initially were misdiagnosed.

One year before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1962, there were 481,530 reported cases nationwide, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2004, there were 37.

Aspiring physicians still learn about the virus in medical school, but they read up on its biology and symptoms at the same time as they're being introduced to a multitude of illnesses they're far more likely to encounter.

"It's not something you spend a great deal of time on at all, for obvious reasons," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Schaffner said he thought the Disneyland outbreak — and the pockets of undervaccinated children that have fueled it — might lead medical schools to increase their emphasis on teaching measles. But the latest generation of doctors still won't get hands-on experience.

"In the bad old days, any grandmother could walk past a child with measles and say, 'That's a child with measles,'" Schaffner said. "It's pattern recognition. And if you haven't seen it before, it can be puzzling."

With measles in particular, which can resemble many other illnesses in its early stages, seeing is understanding, said doctors who had treated afflicted patients. Textbook pictures can't fully convey what the signature rash looks like. Infected kids are uniquely irritable.

"There's a miserableness quotient," said Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and outspoken immunization proponent. "You can read about it, but there's nothing like seeing it."

Sawyer said he recently asked a group of pediatric residents whether they had ever seen measles. None raised their hands.

It's a problem, Sawyer said, because the virus is so contagious.

"There are a lot of infectious diseases physicians don't see in training, but most don't have the same consequences if you miss it for a little bit," he said. "The problem with measles is, if you miss it, you put people at risk."

More than 90% of people who don't have immunity to measles — either through vaccination or from having had the disease — will get sick if exposed to the virus, which can survive for up to two hours in the air.

Dr. James Cherry, a UCLA research professor and principal editor of the Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, said it was important for physicians to remember that fever, cough and runny nose are initial signs of measles. About two days after those symptoms begin, white lesions known as Koplik spots emerge inside the cheek. Only later does the rash appear.

Officials at the Orange County Health Care Agency and the California Department of Public Health said they were working hard to make sure doctors knew what to look for to make a measles diagnosis and to keep providers updated on the current outbreak.

This isn't the first time California physicians have had to educate themselves about measles, said Dr. James Watt, chief of the division of communicable disease control of the state public health agency.

Watt was a pediatrician in training during the outbreak of 1989-1991.

"What I remember very vividly was that all over the hospital there were signs that said, 'Think measles.' There were pictures of children with measles," he said, as well as placards reminding doctors of key symptoms.

Dr. Deborah Lehman, a pediatric epidemiologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, said she first encountered the illness during the late 1980s outbreak, when she was in training at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

Two sisters came to the hospital in the middle of the night suffering from symptoms that she and her colleagues thought must be meningitis.

"Measles was the furthest thing from my mind," she said.

A seasoned pediatrician arrived at the children's bedside in the morning. He made the correct diagnosis right away.

No comments:

Post a Comment