If schools slowed down and focused on a deeper kind of flourishing, they might be more productive (if not very Goveian)

by Melissa Benn, The Guardian, http://bit.ly/1lLwrtM

●●smf’s translation:

GOVEIAN: of or pertaining to the Rt. Hon. Michael Gove, British Conservative Party politician, the Secretary of State for Education and the Member of Parliament for Surrey Heath. Gove’s is a climate change denier whose educational philosophy (and his national curriculum) is definitely+defiantly old school/drill+kill – some scholars decry the curriculum as an “endless list of spellings, facts and rules,” arguing it would “stifle creativity and take the fun out of learning.” http://bit.ly/1jRKPFe “Classic novels Of Mice and Men and To Kill a Mockingbird will be banned from British classrooms because Michael Gove thinks teenagers should study works by British writers.” http://bit.ly/1k6BLGy

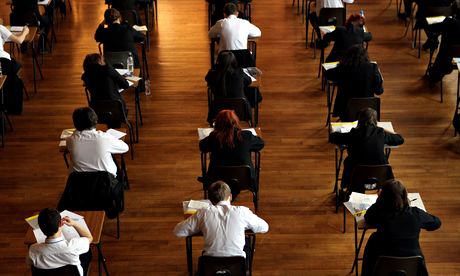

'Educational reform now largely equals intensive schooling: catch-up classes, after-school clubs, longer terms, more testing.' Photograph: David Davies/PA

Wednesday 16 April 2014 11.10 EDT :: Do you know a ghost child? Are you possibly raising one? A report this week by the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) pinpoints a worrying new phenomenon – the institutionalised infant, a whey-faced creature, stuck in school for 10 hours a day, the child of commuting parents possibly, wandering from playground to desk to after-school club without real purpose, nodding off through boredom and fatigue.

The sad thing is, as yet another timely ATL report brings home, the ghost child is increasingly likely to be taught by the ghost adult – a teacher grey with fatigue and stress, stuck at school for 10 hours or more a day, wandering from duty to duty in playground, classroom or after-school club. Both, it seems, are part of a culture that increasingly overworks our citizens, from a younger and younger age, in the often fruitless quest for job security and social mobility.

We know the figures. England is one of the most overworked European nations. What's really new is that we no longer question or even quarrel with this fact. Instead we deploy American-lite righteousness. Work is now not merely a sign of virtue, it is a sign of proper panic, of appropriately anxious aspiration. Any other approach takes you right down benefits street.

Such values have easily transferred to education, where decades of inequality in provision and under-investment have neatly reduced the problems in our system to one of effort, or the lack of it. When a few years ago I interviewed Sir Michael Wilshaw, then still head of Mossbourne academy, he brimmed with anger at "clockwatching" teachers whom he believed had failed to bring poorer pupils on.

Concerns like these have now morphed into a settled theory of education, and childhood itself. Educational reform now largely equals intensive schooling: early-morning catch-up classes, after-school clubs, longer terms, shorter holidays, more testing, more homework.

The trouble is, the human body and human communities do not flourish through being flogged. Families don't benefit from frenetic rushing. They simply forget who each other is, or could be, which is where the real problems begin. Overtired children don't learn. And hungry overtired children simply fall asleep, or kick off.

We could have learned this years ago from some of the most impressive education systems in the world, where children do not start formal learning till as late as seven – and certainly not at two, the scary suggestion now being made by some in government – and where the school day is much shorter. Visitors to some of the Nordic countries, including Finland – still the highest-performing system in Europe – report that it can look as if the children are doing very little in the classroom. There, the educational conversation is all about deep flourishing, enjoyment, stimulation of a different kind.

That makes sense, right? Some of the most productive, and highly professional, people I know work relatively short days and even seem to spend an awful lot of time in contemplation: reading, thinking, staring into space. As one eminent academic said to me, puzzled at so much manic activity in modern living: "I have never worked a 15-hour day in my life."

And the language of effort will not eradicate – only possibly obscure – the educational inequalities that have shifted remarkably little over my lifetime. A poor child on site gets a much-needed breakfast and long hours of subsidised childcare. A better-off child is more likely to be wheeled around to all sorts of extracurricular activities that might make them fractious and overtired but will surely enrich them, in every way, later in life.

This government won't shift gears. It is fully signed up to the ghost road, particularly for the poor. But in other more interesting spaces and places there is a return to ideas that celebrate a different approach to learning, earning and being a human being.

The New Economics Foundation recently proposed that we should make "part time ... the new full time" – that by sharing employment in a time of austerity, with some guarantee on income, of course, we create more time for everyone, old and young alike, to do the things that make us human: spend time with family, friends, take a walk, read a book.

John White, the brilliant philosopher of education, has long argued that "schools [should] be mainly about equipping people to lead a fulfilling life". Anthony Seldon, the master of Wellington College, home of the much-celebrated "happiness lessons", would surely agree.And the wonderful movement for "slow education" stresses the importance of process over pushing, quality over endless quantifying. "The notion of slow ... fosters intensity and understanding and equips students to reason for themselves ... the arts of deliberation are an essential element in this." according to its architect Maurice Holt.

Of course, such notions are utterly unGoveian. Fiendishly Finnish in fact. At their heart is the radical idea that time itself – time to think, time to laugh, time to potter; time at home, time alone – should make a comeback in pedagogical and human discourse. Our growing army of ghost children deserve nothing less.

No comments:

Post a Comment