Transforming our Schools: Readers react to a student’s ideas for a learning ‘revolution.’

Letters to the New York Times/Sunday Dialogue | http://nyti.ms/V0Xjc0

ART: Till Hafenbrak

Published: October 13, 2012

To the Editor:

When President George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind into law, few would have predicted that the next decade of education policy would unfold into a disaster of epic proportions. The law was based on a flawed concept of a “good education” — high scores on standardized tests.

As a result, the curriculum was narrowed, shaving instruction time in the arts, music, science and history. Schools were transformed into test-preparation factories with a stress on drill, kill, bubble-fill methods. And ruthless accountability measures were enacted, with bribes and threats at their core. It’s safe to say that the law has failed miserably.

Yet when President Obama came into office, he enacted Race to the Top, a $4.35 billion competition that dished out money to states that adopted the president’s policies. In effect, it was No Child Left Behind on steroids. The pressure to garner high test scores has gone haywire, the number of cheating scandals has mushroomed and the teaching profession has been dehumanized. Enough is enough.

In this election cycle, both Mitt Romney and President Obama have largely ducked the issue. Instead of proposing a bold, game-changing plan to transform schools for the 21st century, they remain stubbornly fixed on the status quo. We cannot afford to lose yet another decade of precious time and resources. Reforms are not enough; only a revolution will suffice.

As a student, I want to be taught how to think and create and explore. I’m not a number in a spreadsheet; I’m a creative and motivated human being. I want my teachers to be paid well, given autonomy and treated like professionals. I want my school to be adequately funded. Is that too much to ask?

As a student, I want to be taught how to think and create and explore. I’m not a number in a spreadsheet; I’m a creative and motivated human being. I want my teachers to be paid well, given autonomy and treated like professionals. I want my school to be adequately funded. Is that too much to ask?

If either candidate called for the repeal of No Child Left Behind and the abolition of Race to the Top, and pushed schools to allow students to become the captains of their learning, he would find millions of teachers, parents and young people at his side.

NIKHIL GOYAL

Syosset, N.Y., Oct. 8, 2012

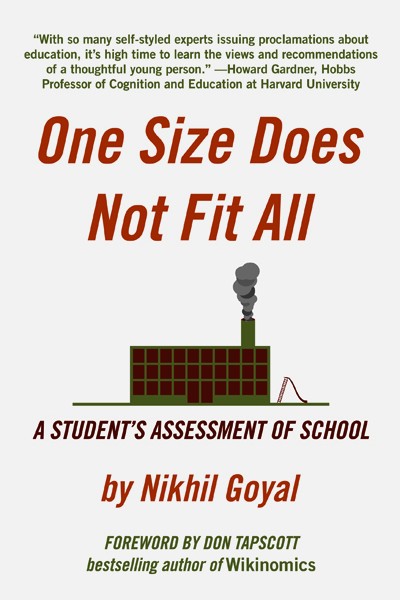

The writer is a high school senior and the author of the book “One Size Does Not Fit All: A Student’s Assessment of School.”

Readers React

Mr. Goyal points out an essential and alarming feature of the politics of education: It’s the one place where Democrats and Republicans have been willing, even eager, to embrace the same ideas. For all the talk of the benefits of bipartisanship, this signature effort has been an unmitigated disaster for American schools. If anything, Mr. Goyal understates the extent of the damage.

The greatest danger of the accountability movement is that it shifts the conversation away from the real needs of American schools. It is much easier to talk about test scores than it is to advocate adequate and equitable school funding, strong early intervention programs, and a highly qualified, professionalized and well-paid teaching force.

Perhaps this explains bipartisan support for an educational system of, by and for tests. For politicians who wish to avoid accountability for the state of our schools, the accountability movement is the right answer.

STEVEN K. WOJCIKIEWICZ

Monmouth, Ore., Oct. 10, 2012

The writer is an associate professor of teacher education at the Western Oregon University College of Education and a former high school teacher.

Mr. Goyal does not speak for all students. I am a high school senior and was involved in protesting Connecticut’s education reform bill on the principle that the way it approached testing was wrong — something I wholeheartedly agree with Mr. Goyal on. But not every student believes that standardized testing is the devil or that the American education system is designed to suppress us.

The answer, as I see it, is not to eliminate testing. Nor is it to eliminate federal standardization of curriculums or objective evaluation of schools — all things Race to the Top and No Child Left Behind strive to do. Let’s fix what’s broken — our tests — by pushing for better, smarter tests, not eliminating them.

ANDREW BOWLES

Westport, Conn., Oct. 10, 2012

I don’t need to look at Mr. Goyal’s eighth-grade English language arts test score, or how he fared on his high school Regents exams, to know that he is a smart and critical thinker, that he is a “creative and motivated human being.” This is glaringly obvious even from his short letter. So why is it that many policy makers and education wonks believe that they need to?

What these policy makers should be doing is looking to students like Mr. Goyal to figure out new ways to solve our most pressing education policy problems. Organizations like Urban Youth Collaborative in New York City harness the power, and insider school knowledge, of local students to challenge the educational status quo. Rather than seeing students as a statistic or a test score, they understand them as valuable sources of policy insight.

Let’s stop patronizing young people with lackluster standardized testing and start treating them as a source of expertise in education that could shed some light on how to fix this mess we created.

TARA BAHL

New York, Oct. 10, 2012

The writer is an adjunct professor of education at Mercy College.

Surely Mr. Goyal sees the irony in demanding that his affluent Long Island suburban school district, Syosset, be adequately funded and its teachers well paid. Public schools in low-income communities and many of our urban areas haven’t fulfilled their promise of a basic education in decades.

Our system of school funding primarily through property taxes does a disservice to the students whose only crime is to live in a less wealthy district. In March 2011, an editorial in this paper (“Rich District, Poor District”) detailed this disparity by comparing the Syosset district with that of Ilion, in an economically depressed area of New York.

Until we commit to a truly level playing field, in which our public schools are funded solely on a national scale, students like Mr. Goyal will always have an unfair advantage over those in Ilion.

JONATHAN CAREY

San Francisco, Oct. 10, 2012

I agree with the concern over the very poor results we get for the billions of dollars spent on education in the United States. The attempt by the government to impose some standards was well intended, but as Mr. Goyal pointed out, did not work, twice.

The fundamental problem with education is the government’s involvement, and consequently no market dynamic. Give parents and students a choice, as private schools always do, and voucher systems tend to do, and education thrives because there is real accountability. Bad schools, like bad businesses, go away, because they have no customers and are unable to compete.

Technical colleges, community colleges, universities and other forms of education that are market-based are doing just fine. Find a way to bring choice and competition into grade school and high school education, as some communities have done with voucher programs, and the market will solve the education problem.

BILL FOTSCH

Villa Hills, Ky., Oct. 10, 2012

I’m a college student and future teacher who is deeply committed to educational equity and social justice, but I was incredibly frustrated by Mr. Goyal’s piece. While Mr. Goyal highlights some of the issues affecting our education system, his letter lacks nuance and makes several overstatements.

As a student, I too want to be taught “how to think and create and explore.” But I also realize that if I couldn’t read or write or do basic math, I’d have a lot of trouble making it to college — much less finding a job that pays the bills.

As a future teacher, I want to be held accountable for my students’ learning. Certainly, “learning” can’t be boiled down to a fill-in-the-bubble test, but when used as part of a holistic and balanced evaluation system, standardized test scores can add value. I wouldn’t feel “dehumanized,” as Mr. Goyal suggests, if I were assessed against quantitative and qualitative measures.

Moving forward, we students need to realize that things aren’t as simple as they seem. Let’s approach these issues with a sense of humility and ambivalence.

RYAN HEISINGER

College Park, Md., Oct. 10, 2012

I have two children in middle school. Why does it seem to me that while there is so much more to learn today, my children are learning less and spending more time and requiring tutors to do so? Why were my children taught fuzzy math? How much more can we dumb down the next generation?

When is the government going to require schools to step up to the plate and teach? Stop teaching my children to simply spit back answers, and stop using them as guinea pigs to try out the latest math program from a company that just wants to make money. Teach them how to think.

SUSAN ZAHLER

Plainview, N.Y., Oct. 10, 2012

Reading “A Student’s Call to Arms” both shocked and saddened me. When my sons were starting school over 30 years ago, we specifically chose a school that was run on Mr. Goyal’s vision, to educate children rather than to test them.

Mr. Goyal’s letter certainly describes a backward slide of mammoth proportions. Education is too important to leave to lazy politicians who would quantify it in order to proclaim success.

SIDNEY S. STARK

New York, Oct. 10, 2012

The Writer Responds

I agree with Mr. Bowles that we need better ways of measuring students. However, testing isn’t one. Assessment is. There’s a difference. A test is used to tell whether a student memorized and regurgitated enough material. Interestingly, the man who invented the multiple choice test, which is now ubiquitous, later denounced it as a “test of lower order thinking for the lower orders.”

An assessment, on the other hand, is an ongoing process of describing, gathering, recording and reflecting. Schools like High Tech High in San Diego and Brightworks in San Francisco are leveraging the power of assessments, using digital portfolios to reflect students’ work — blog posts, essays, podcasts, presentations. This is in line with the argument by Ms. Bahl. When we begin to shift the way we assess students, then we will witness true learning and creativity.

To address accountability, which Mr. Wojcikiewicz stressed, we should sample rather than assess every single student, similar to what Gallup does with public opinion surveys.

If we’re going to bring about a learning revolution in America, we need to do a lot more to change the conversation. Let’s push our politicians with common-sense ideas: finance schools adequately, evaluate students and teachers appropriately, treat students like adults, allow student-centered, project-based learning to flourish, and invigorate the gush of creativity and curiosity within us all.

President Obama, Mitt Romney, are you listening?

NIKHIL GOYAL

Syosset, N.Y., Oct. 12, 2012

____________________

Want to Ruin Teaching? Give Ratings

By DEBORAH KENNY, NY Times Op-Ed Contributor | http://nyti.ms/RrbRRc

By DEBORAH KENNY, NY Times Op-Ed Contributor | http://nyti.ms/RrbRRc

Published: October 14, 2012 :: AS the founder of a charter school network in Harlem, I’ve seen firsthand the nuances inherent in teacher evaluation. A few years ago, for instance, we decided not to renew the contract of one of our teachers despite the fact that his students performed exceptionally well on the state exam.

Rose Blake>>

We kept hearing directly from students and parents that he was mean and derided the children who needed the most help. The teacher also regularly complained about problems during faculty meetings without offering solutions. Three of our strongest teachers confided to the principal that they were reluctantly considering leaving because his negativity was making everyone miserable.

There has been much discussion of the question of how to evaluate teachers; it was one of the biggest sticking points in the recent teachers’ strike in Chicago. For more than a decade I’ve been a strong proponent of teacher accountability. I’ve advocated for ending tenure and other rules that get in the way of holding educators responsible for the achievement of their students. Indeed, the teachers in my schools — Harlem Village Academies — all work with employment-at-will contracts because we believe accountability is an underlying prerequisite to running an effective school. The problem is that, unlike charters, most schools are prohibited by law from holding teachers accountable at all.

But the solution being considered by many states — having the government evaluate individual teachers — is a terrible idea that undermines principals and is demeaning to teachers. If our schools had been required to use a state-run teacher evaluation system, the teacher we let go would have been rated at the top of the scale.

Education and political leaders across the country are currently trying to decide how to evaluate teachers. Some states are pushing for legislation to sort teachers into categories using unreliable mathematical calculations based on student test scores. Others have hired external evaluators who pop into classrooms with checklists to monitor and rate teachers. In all these scenarios, principals have only partial authority, with their judgments factored into a formula.

This type of system shows a profound lack of understanding of leadership. Principals need to create a culture of trust, teamwork and candid feedback that is essential to running an excellent school. Leadership is about hiring great people and empowering them, and requires a delicate balance of evaluation and encouragement. At Harlem Village Academies we give teachers an enormous amount of freedom and respect. As one of our seventh-grade reading teachers told me: “It’s exhilarating to be trusted. It makes me feel like I can be the kind of teacher I had always dreamed about becoming: funny, interesting, effective and energetic.”

Some of the new government proposals for evaluating teachers, with their checklists, rankings and ratings, have been described as businesslike, but that is just not true. Successful companies do not publicly rate thousands of employees from a central office database; they don’t use systems to take the place of human judgment. They trust their managers to nurture and build great teams, then hold the managers accountable for results.

In the same way, we should hold principals strictly accountable for school performance and allow them to make all personnel decisions. That can’t be done by adhering to rigid formulas. There is no formula for quantifying compassion, creativity, intellectual curiosity or any number of other traits that make a group of teachers motivate one another and inspire greatness in their students. Principals must be empowered to use everything they know about their faculty — including student achievement data — to determine which teachers they will retain, promote or, when necessary, let go. This is how every successful enterprise functions.

A government-run teacher evaluation bureaucracy will make it impossible to attract great teachers and will diminish the motivation of the ones we have. It will make teaching so scripted and controlled that we won’t be able to attract smart, passionate people. Everyone says we should treat teachers as professionals, but then they promote top-down policies that are insulting to serious educators.

If we don’t change course in the coming years, these bureaucratic systems that treat teachers like low-level workers will become self-fulfilling. As the great educational thinker Theodore R. Sizer put it, “Eventually, hierarchical bureaucracy will be totally self-validating: virtually all teachers will be semi-competent.”

The direction of education reform in the next few years will shape public education for generations to come. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has repeatedly said that in the next decade, “over 1.6 million teachers will retire,” and our country will be hiring 1.6 million new teachers. We will blow that opportunity if we create bureaucratic systems that discourage the smartest, most talented people from entering the profession.

Deborah Kenny is the chief executive and founding principal of Harlem Village Academies and the author of “Born to Rise: A Story of Children and Teachers Reaching Their Highest Potential.”

No comments:

Post a Comment